What Does A Massage Gun Do? (Science Explained!)

Massage guns — the latest overpriced and overhyped fitness product.

Around December 2020, when these things hit their peak popularity, multiple massage gun companies started emailing me, offering to sponsor a video if I reviewed their product.

And while I’ve personally tried these products in the past, I wasn’t willing to take on any of them as sponsors until I researched them.

If I endorse something, I want to know it’s legit, and unfortunately, my research did not support the claims that advertisers made.

But I figured I’d share the results with you all, and more importantly, share my research process.

So do massage guns really work?

Well, it depends on what you mean by work.

Right away when we’re evaluating whether a product’s claim is true, we need to clarify what the claim /is/.

If I go on Amazon and look at the product descriptions for massage guns, I see a few claims, the most common of which is that these massage gun helps reduce recovery time, increase range of motion, promote blood flow, and relieve chronic pain.

So the first thing I do is a search on PubMed and start looking for any systematic reviews about massage guns — or percussive therapy, as it’s called in the literature.

If you’ve never heard of reviews before, they’re an attempt to systematically analyze, critique, and synthesize all scientific information about a specific topic into one, up-to-date source.

It’s an attempt to answer the question “What is everything we know about this thing?”.

By doing that, we eliminate the ability for people to cherry-pick studies that support their claims.

Next, I widened my scope to include all research formats in PubMed, and I found that, as of July 2021, there were only 2 peer-reviewed studies that looked at people who used these tools, both of which were published in 2020.

Research

The first article was a case study published in the Physical Therapy and Rehabilitation Journal in 2020.

Case studies are basically stories — they document noteworthy and interesting cases.

This one tells the story of a 25-year-old woman who got rhabdomyolysis, a potentially lethal condition where injured muscles break down and dissolve. After training on a stationary bike for 30 minutes, her coach used a massage gun on her thighs, assuming that it would relax her muscles.

He wasn’t a trained massage therapist and didn’t take a medical history before using it. It turns out his client was anaemic, which might have predisposed her to rhabdo.

Now, overexercising can be one of the triggers of rhabdomyolysis, but this woman only did a few minutes on a stationary bike and had tolerated it well before.

So the author suggests that the mechanical trauma from the percussion gun caused her muscles to break down — although we’ll never know exactly how the trainer used it.

Fortunately, after a few weeks in the hospital, she recovered. But reasonably, the article concluded with “hey, these things are potentially dangerous if used wrong”.

But it’s a case study, so that doesn’t mean everyone’s muscles will start falling apart, just that it has happened.

Our second article was a randomized controlled trial, where the researchers split participants into two groups, one of which gets the treatment, one of which doesn’t.

This last group is called the Control Group. This is considered the gold standard of experiments since any difference between the groups is likely because of the treatment.

This article was published in the Journal of Sports Science and Medicine and looked at whether massage guns could improve range of motion. Perfect.

This is one of the claims made by most advertisers.

The researchers recruited 16 young men to come in on two separate days and measured their dorsiflexion range of motion. Then they gave them either 5 minutes of massage gun treatment to their calf, or no treatment at all.

Then they measured dorsiflexion again to see if there was any change — they also measured maximum force production with a special machine.

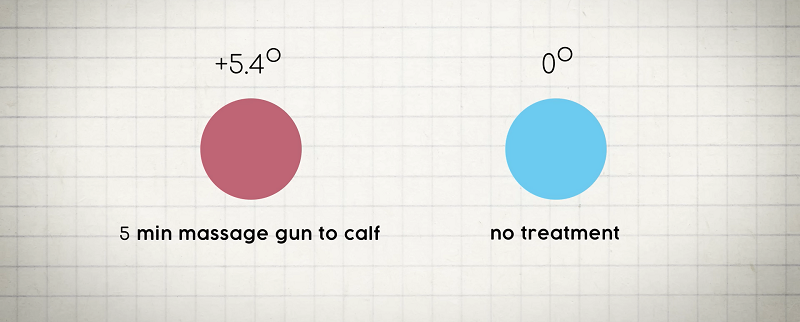

They found that the treatment group’s dorsiflexion increased by an average of 5.4 degrees, while there was no difference in the control group.

Force production was unaffected either way, so they suggested that this kind of treatment might be appropriate during warmups to increase the range of motion before activity.

While that supports at least one of the claims we talked about, we need to be careful of what it doesn’t support. They only measured acute effects in this study — what happened right after treatment. We’d need to repeat this on the order of weeks to say whether consistent massage gun treatments increase the range of motion over the long term.

Plus, they also only used young, healthy men in their study, and only measured one joint.

That doesn’t automatically mean that this treatment will work for older adults or for more complex joints like hips and spines.

Plus, (and this is my favourite part) this same research group did this exact same experiment in 2019 except they tested static stretching instead of massage guns, and they saw the same effect on range of motion.

The free intervention was just as effective at increasing the acute range of motion as the $300 option.

Now, those are the two peer-reviewed studies I found on PubMed, and if I were conducting a proper systematic review or writing a SciShow script, I’d check out some other databases.

But for now, I’m just getting a lay of the land.

And clearly, these two studies don’t lend a ton of support to our big advertising claims from the beginning, which is normal.

It’s common for advertisers to steal claims from related therapies and repurpose it for their own.

Massage gun sellers base their claims on the research done on manual massage therapy, with the /assumption/ that the same conclusions for massage can be applied to massage guns.

Now, that’s not how science works.

While these modalities are /intended/ to do the same thing, we don’t /know/ that they accomplish the same thing unless we study it.

In our little research so far, we’ve only found evidence for an improvement in range of motion, but I’m still curious about this big claim — muscle recovery.

So I looked for reviews on massage therapy and recovery and found way more results.

This is understandable, massage therapy has been around for thousands of years while massage guns have not.

A review from 2008 in the Clinical Journal of Sports Medicine looked at muscle recovery in human subjects who performed strenuous exercise and got a massage at some point — perfect for what we’re looking for.

Muscle recovery was usually measured by having the participant rate how sore or painful their muscles felt, and might have included data about range of motion or peak torque production.

All in all, they included 27 articles, 10 of which were those high-quality randomized controlled trials. The 17 other studies were case series — basically where a researcher said “I massaged a bunch of people and here’s what I saw”.

Case series almost never use control groups.

But each study was different.

They used different massage techniques and massaged different muscles for different lengths of time.

Plus, very few studies measured an objective measure of soreness — most asked for a subjective rating of pain.

The other elephant in the room is that participants know if they’re getting massaged or not, and that might bias them.

Likewise, the researchers know who got massaged. And in a traditional RCT, neither the participants nor the researchers would know which treatment the participants were getting until the very end, this is called blinding.

So while the writers of the review wanted to find out whether massage helped with muscle recovery, the studies were just too different to learn anything conclusive.

But they did pull out some useful info.

Like, that the most recovery happened if the treatment was within a two-hour window after exercise. The duration of the massage, ranging from 5 minutes to 30 minutes, didn’t impact recovery.

A more recent review has come out since then. It was published in the British Medical Journal Open Sport and Exercise Medicine in 2020, and not only did it include all the more recent studies, but it also ran what’s called a meta-analysis.

Basically, it compiles all the studies on a topic and pools their data together to find stronger patterns using the new, bigger pool of participants. And just like a review, they have to be pretty specific about the questions they’re asking.

This meta-analysis looked at studies that measured the effect of massage on sports performance, including strength, flexibility, and recovery.

All in all, they looked at 12 randomized controlled trials and 17 randomized crossover studies, which encompassed over a thousand participants.

When combining all that data together, they found that massage had no effect on most metrics of performance like sprint time, endurance, or strength but significantly improved flexibility scores by about 7%.

And while massage didn’t have any effect on muscle fatigue, it did significantly reduce delayed onset muscle soreness, or DOMS by 13% — this is probably the thing that advertisers will point to to justify the “promotes recovery” claim.

But again, that’s a subjective measure, and one of the studies was a heavy outlier, which inflates the average.

And bringing it back to the original premise of the article, this meta-analysis only speaks to massage therapy.

We can’t assume this translates to massage guns.

So, the final thing I look for when checking out these products or therapies is a proposed mechanism for how it works physiologically.

Luckily, I found an article published in 2005 that reviewed the proposed mechanisms behind massage.

They collected a bunch of journal articles and found that proposed mechanisms fell into 4 categories: biomechanical, physiological, neurological, and psychophysiological mechanisms. And right away, there was limited evidence to support most of them.

For instance, people have proposed that massage decreases active muscle stiffness, but /no/ studies have ever checked.

Others proposed it decreased /passive/ stiffness, but only one study checked, and it didn’t have any significant effect past the control group.

Meanwhile, some studies found a positive effect of massage on a range of motion, but often they didn’t have appropriate control groups or they couldn’t blind their subjects like I mentioned earlier.

Plus, when compared to static stretching, massage was only able to increase dorsiflexion, while static stretching increased the range of motion across all lower extremity measurements.

So massage is fine, but so is stretching.

In the physiological category, there /is/ good evidence that massage increases skin and muscle temperature a little bit, but the big suspected mechanism, increased blood flow /didn’t/ have a ton of good evidence.

Most studies used small sample sizes and didn’t analyze any statistics.

Plus, some of the more advanced tools that physiologists use to measure blood flow, tend to overestimate blood flow.

The best research (ie, the studies with the least amount of design problems) showed no change in the blood flow to muscles after massage.

So massage might work because it provides heat. But we can’t say it increases blood flow with any certainty.

The psychological mechanisms were probably the most compelling category.

FAQs

Q1: How much time to use a massage gun?

A: Usage time for a massage gun varies depending on the muscle group and purpose. As a pre-workout routine, spending one to two minutes massaging each muscle group you plan to exercise directly, plus 30 seconds on supporting muscle groups, is suggested.

Q2: What do massage guns do?

A: Massage guns, also known as percussive therapy devices, provide deep tissue massage through rapid and repetitive pulsating motions. They help to target specific muscle groups and stimulate blood flow.

Q3: Are massage guns good for you?

A: Massage guns can be beneficial for muscle recovery, reducing muscle tension, and promoting relaxation. They are often used by athletes seeking relief from muscle soreness.

Q4: Are massage guns worth it?

A: Massage guns can be a useful recovery tool for muscle soreness and relaxation. One study suggests that percussive massagers, like massage guns, can provide similar benefits to a 15-minute massage in as little as two minutes of use.

Q5: Are massage guns good for back pain?

A: Massage guns can be helpful for back pain relief as they can target specific muscles and promote relaxation. However, it’s important to use them properly and avoid applying excessive pressure on sensitive areas or the spine. If you have chronic or severe back pain, it is recommended to consult with a healthcare professional.

Q6: Can a massage gun help knee pain?

A: While massage guns can aid in promoting muscle recovery and reducing muscle tension around the knee area, they may not directly address underlying knee pain causes.

Q7: Do massage guns help build muscle?

No, massage guns do not directly help build muscle. They can aid in muscle recovery and reduce muscle soreness, but muscle building primarily requires progressive resistance training and proper nutrition.

Takeaway?

If you like using massage guns and find a benefit in them personally, awesome, have fun.

I’m glad you’re finding a way to enjoy your corporeal form before you collapse and return to dust.

As I mentioned, there’s more research available on some of the other databases, but based on my research so far, the evidence that /does exist/ only supports improvements in range of motion in one muscle group, which you can achieve in the same degree by stretching.

Which is free! So my end message is this: if you’re on the fence about buying one of these things, save your money.

They’re not a miracle cure for anything.

Thanks for reading.